February 10, 2026 at 10:50 AM

Hi Everyone,

Since the last update I:

- Expanded my LinkedIn following significantly

- Spent a few weeks completing a project that involves a variety of robotics concepts

- Began making daily educational posts on LinkedIn based on that project

- Started mentoring my first client - I think it’s going well!

As of the last update, I had started making educational posts on LinkedIn from the Robotics Prep page, and was trying to figure out how to improve their reach. I was also thinking about how to create the posts more efficiently, and publish them with a more logical ordering.

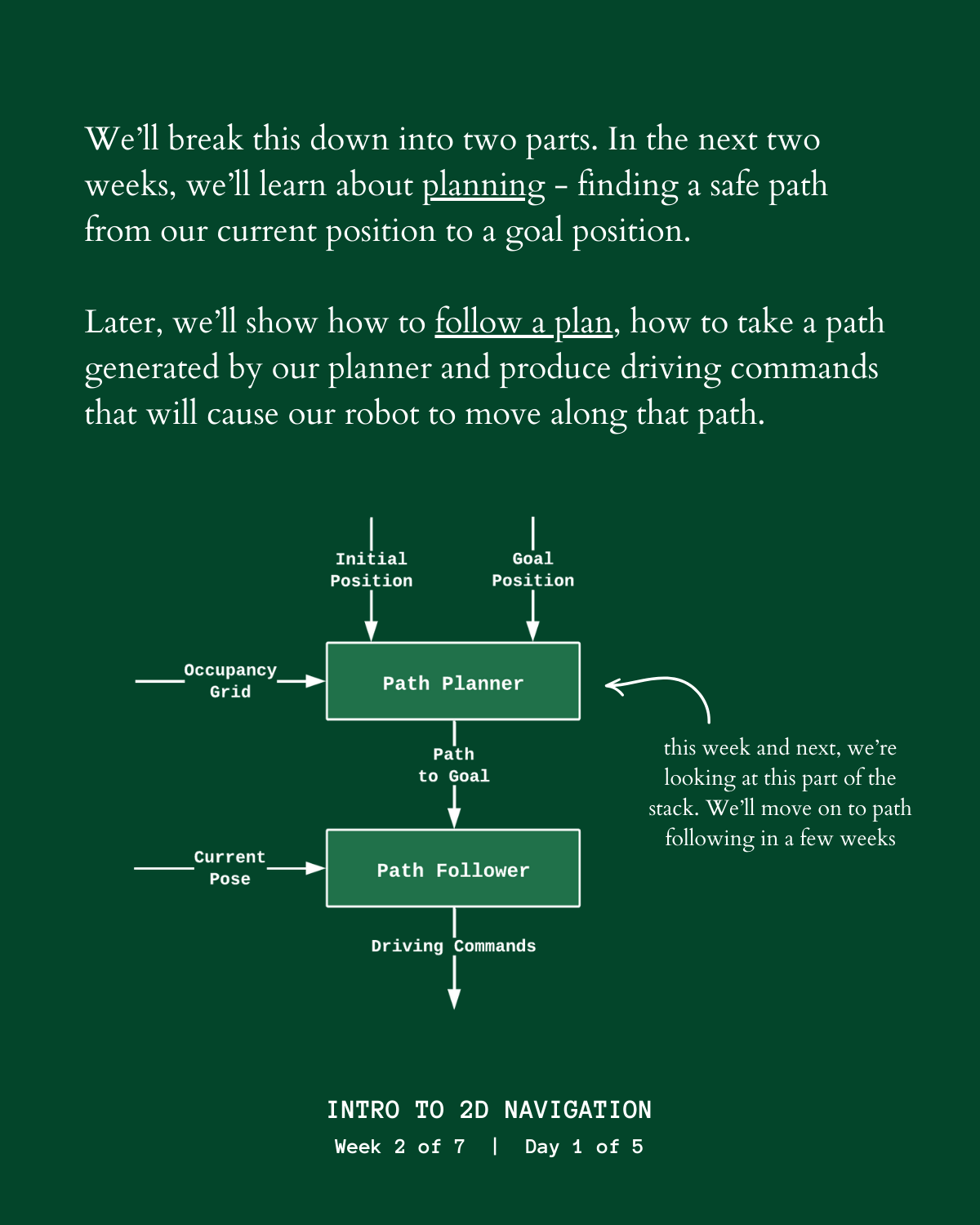

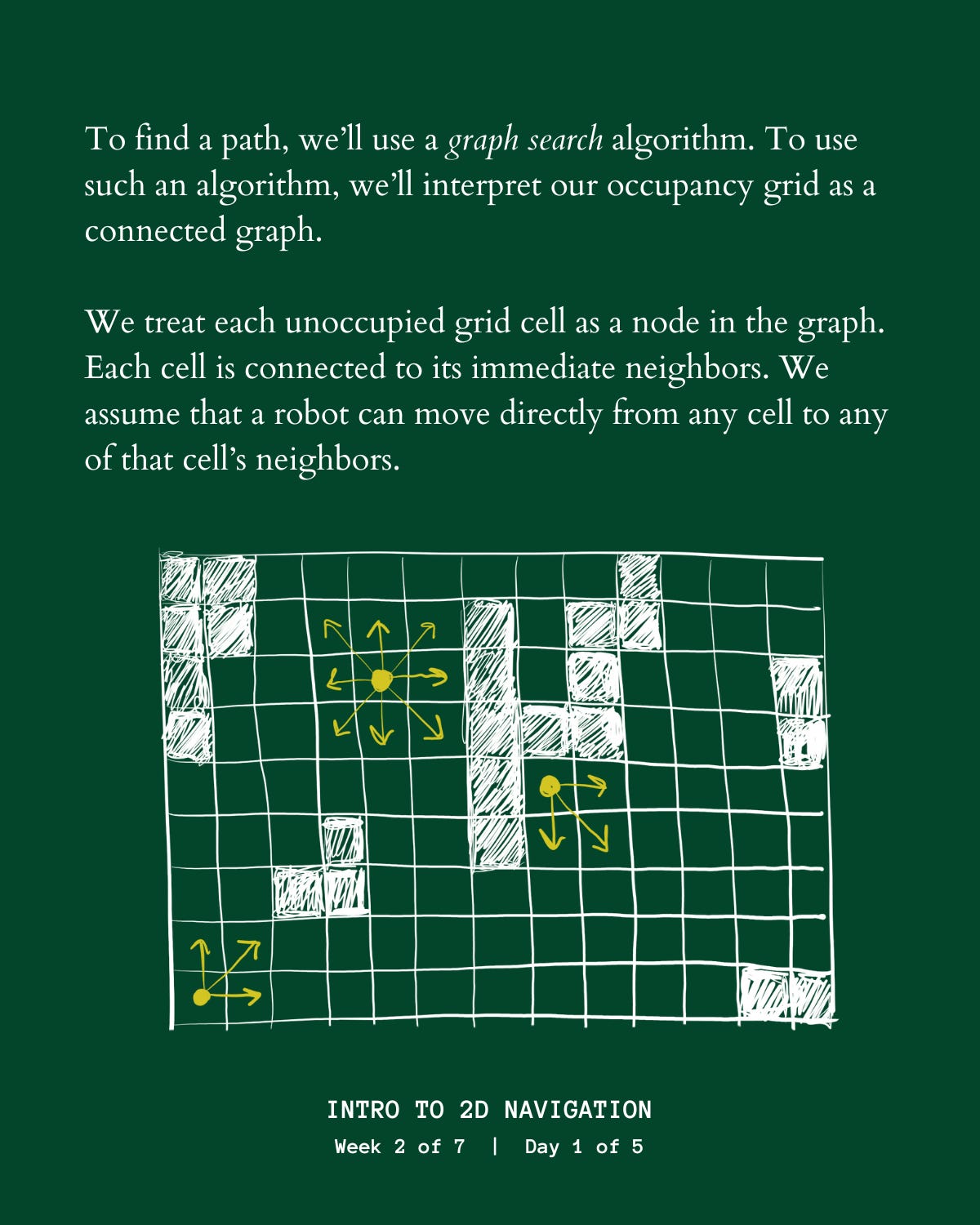

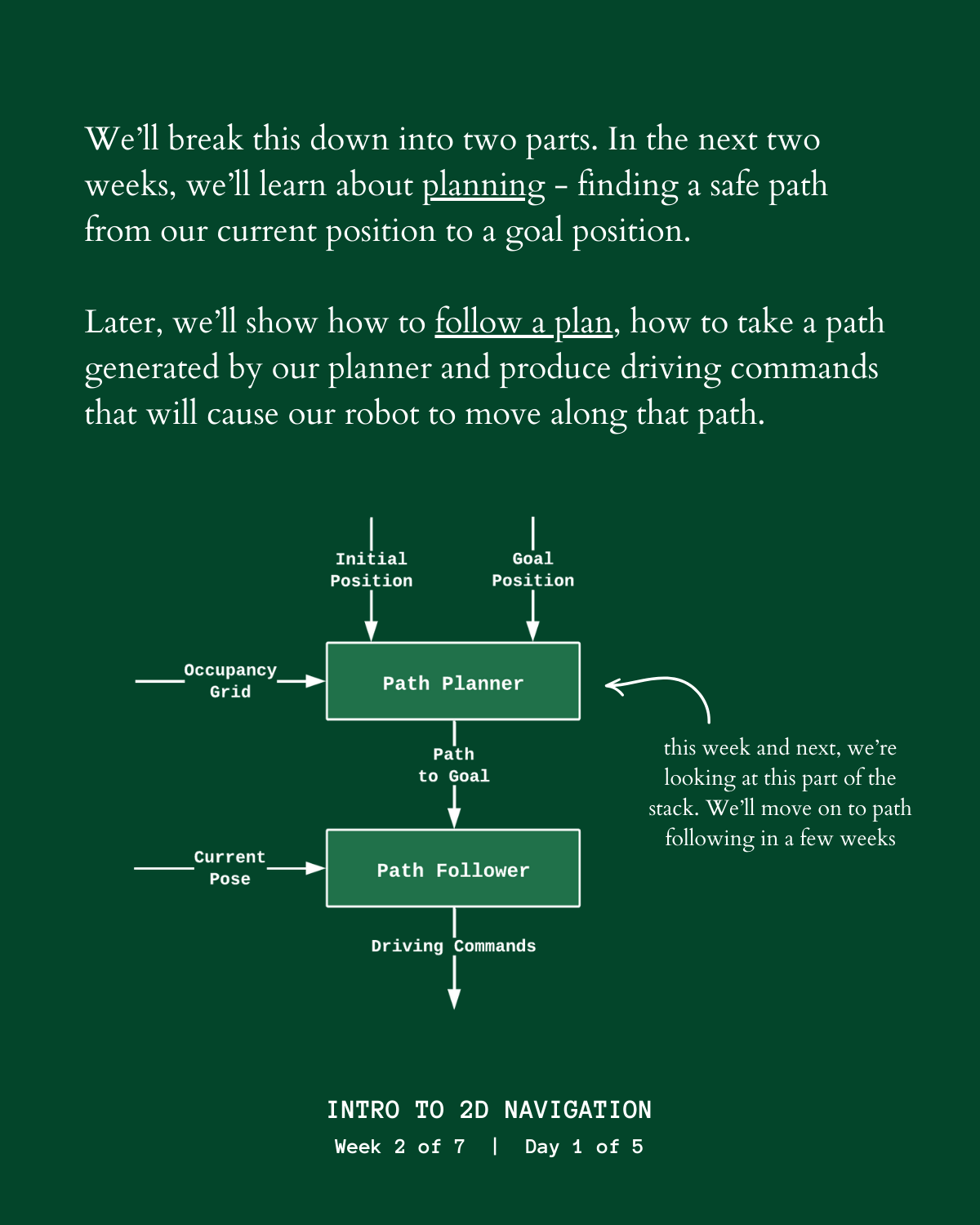

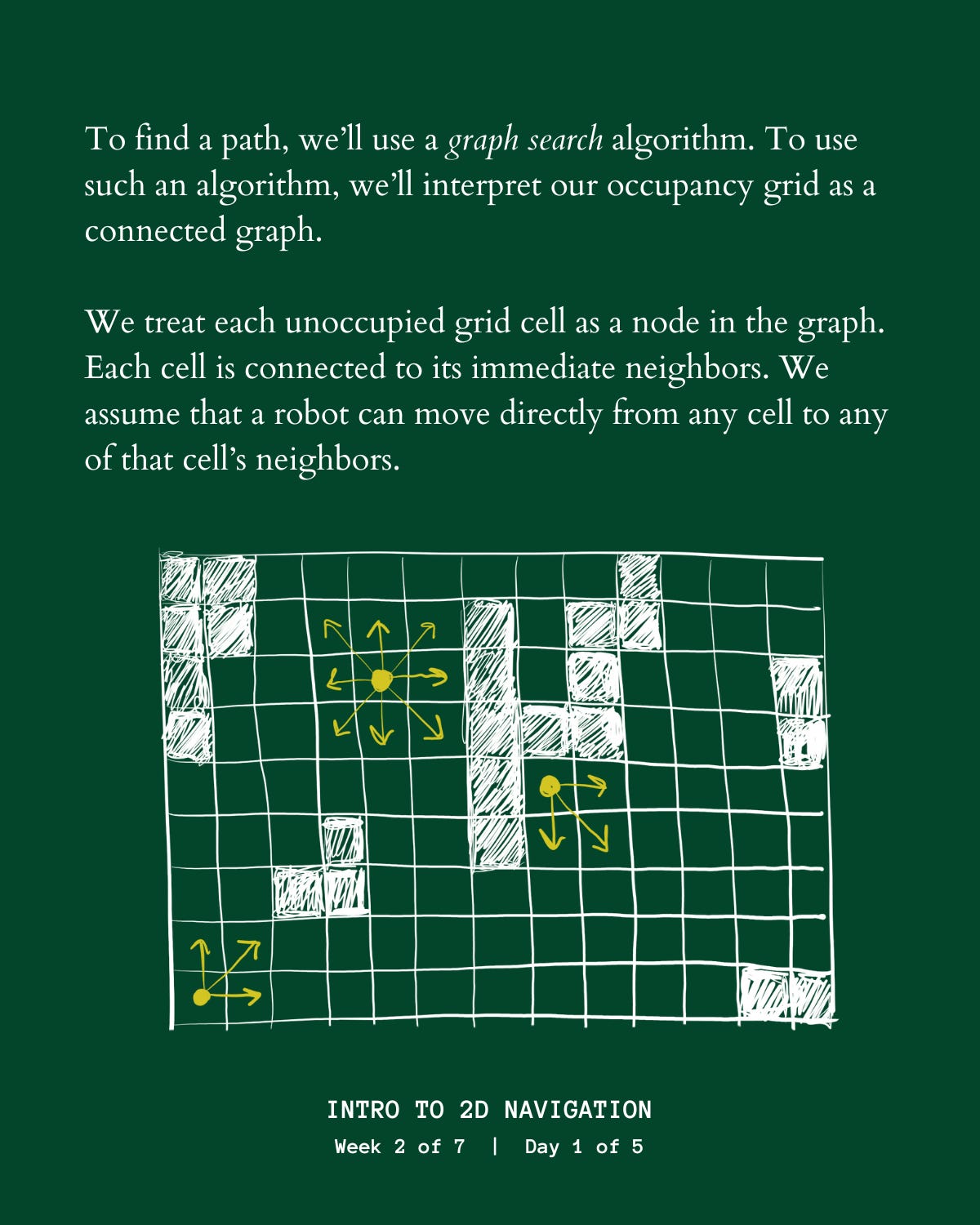

I took the next two weeks to complete a mini robotics project, a simulator for a robotics navigation stack that allows a simulated robot to drive between different points on a map. Once I had the project working, I made a list of all the topics that you’d need to know in order to build something similar from scratch. Then I planned out 7 weeks worth of posts that explain all of those topics. I published the first week of posts last week, and am sending out the second batch this week.

The posts still take a while to create, but I'm getting faster - it now takes one or two days to create a full week of posts, which is freeing up more time for me to work on other things.

For the last three weeks, I’ve been methodically expanding my LinkedIn network, specifically among people in the robotics industry. Every morning, I send out 15 connection requests to people who I have mutual connections with. I’d estimate that about 10 / 15 of those requests are eventually accepted. Since my last update, my follower count has grown from 290 to 600, with all of the new following coming from the robotics industry. My hope is that when I post things about robotics or advertise my services, those posts will get high engagement among my network, being especially relevant to that audience.

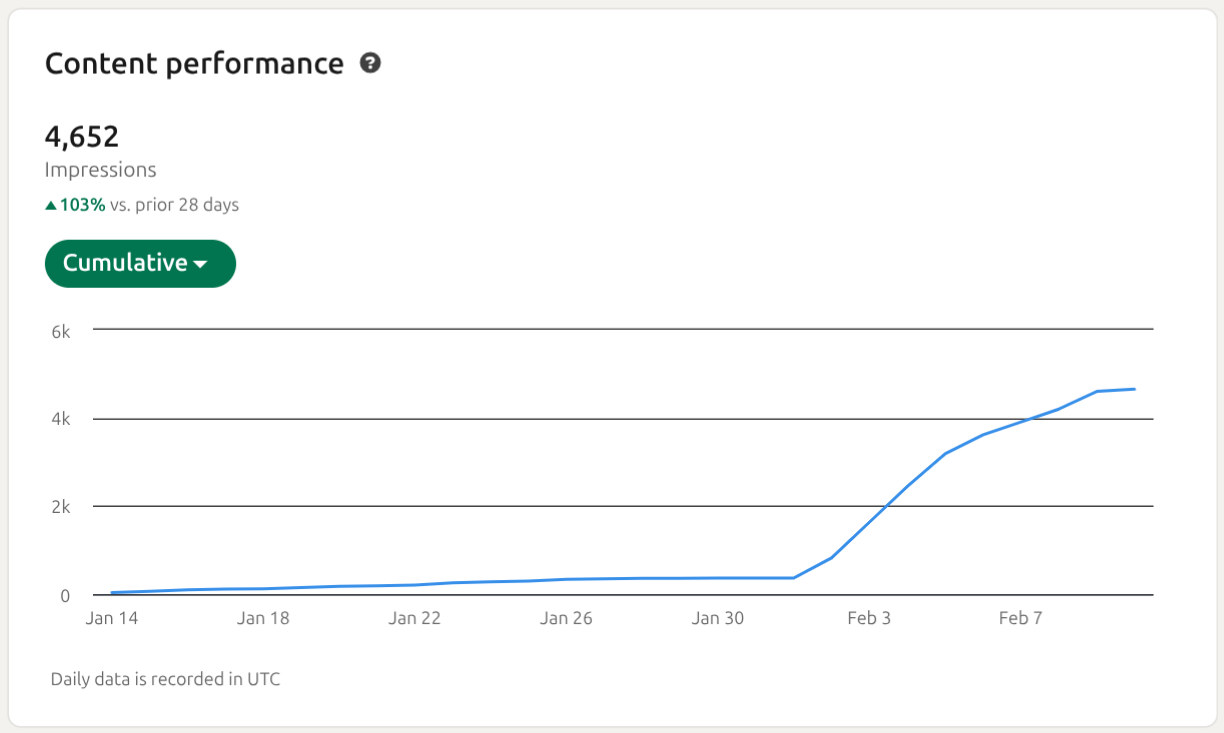

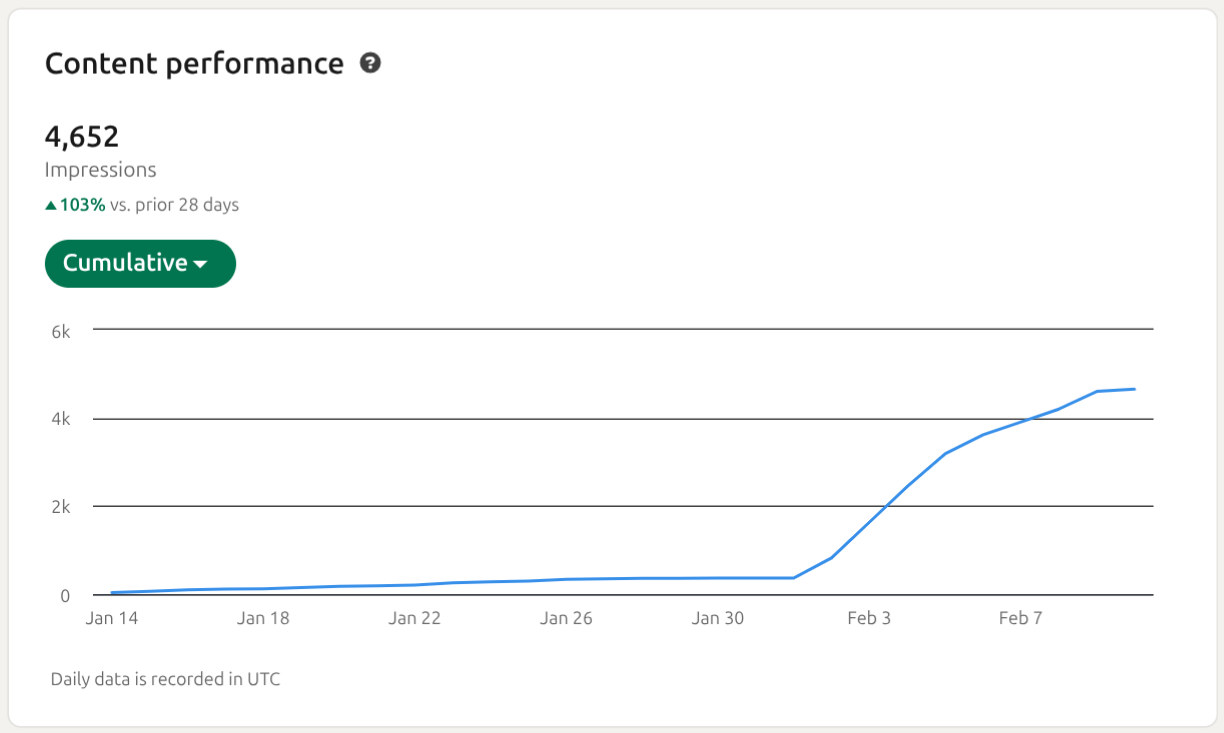

The educational posts from the Robotics Prep page continue to get extremely good engagement (% of people who see the post who stop to read it), but poor reach (# of people who are shown the post). I mentioned in the last update that the algorithm heavily prioritizes posts from personal accounts over pages, so this isn’t really surprising. The post I published from my personal account, kicking off the ‘Intro to Navigation’ series did really well - over 4,000 views with high engagement.

My social media plan seems to be going well in the sense that my reach is increasing and my posts are engaging. The question now is whether I can turn that into paying customers. None of my posts from the last few weeks have mentioned my services at all, they’ve been strictly educational, so it’s unsurprising that they haven’t driven any interest in the mentorship program.

In the next few weeks, I’ll publish a few posts that directly explain my mentorship program, and make the case that people should sign up for it. If the offer is compelling enough that it could make a real business, I would expect this to lead to at least a few more signups within the next few weeks. If my offer is reaching a large, relevant audience, but still not driving any customers, I’ll need to rethink the offer.

The last update is that I’ve been mentoring my first client for a few weeks now and I think it’s going well! I’ve done several technical practice sessions to help him prepare for interviews, and have created a variety of other materials to help him use his study time efficiently. I think he’s on track to land a job before too long.

I’m also learning a lot about how to run a program like this. I think the mentee experience is good already (I feel very confident that my client is getting significantly more value than the price they paid) but there are lots of things I can do to make it even better for future clients.

Until next week (or possibly 2 or 3 weeks from now, who knows),

Jake

January 18, 2026 at 9:51 AM

Hi Everyone,

Since the last update I:

- Created daily educational posts on LinkedIn

- Thought about how to improve my outreach strategy for next week

- Gained my first client for the career mentorship program

To recap my high-level growth plan:

- I post useful, education robotics stuff on LinkedIn (and eventually other platforms)

- I build a large following among robotics people

- Some of those people visit and use the Robotics Prep website

- Some of the website visitors sign up for the mentor program or practice interviews

My first goal for this week was to create some kind of educational robotics post for LinkedIn each weekday. I didn’t have an overarching plan for what each post would be about entering the week, but in the process of creating the first few, I figured out a formula I’ll use for the next few weeks. This week’s posts included:

M: Kinematic bicycle model explainer (part 1)

Tu: Coding challenge prompt, with a video demoing a working solution

W: Explanation of terminology related to robot motion

Th: Kinematic bicycle model explainer (part 2)

Fri: Practice interview questions

Here's an example of the style of post I've been creating:

Most of the posts were connected to the same topic (modeling the motion of a vehicle). This week I was sort of figuring that out as I went - for next week, I’m going to pick a topic up front, plan out all the posts, and will also try to create them all in one go, rather than one per day.

While this week my focus was on producing a post each day, my focus for the next week will be improving the reach of those posts. To do that, I’m going to try the following strategies:

- The 5 weekly posts will all be connected and cover the same, specific robotics topic. I’ll label the posts to indicate the order in the sequence. These will be posted to the company page

- I’ll make multiple posts from my personal account summarizing what the topic is for the week and including an interesting visual - ChatGPT says that company pages are not favored by the LinkedIn algorithm and that early on, most of the outreach should come from a personal account. I’ll mention the company / company page in the posts and hopefully direct some of the traffic there

- I will proactively connect with robotics engineers on LinkedIn and try to build my network through ‘brute force’

- I will comment on posts of other robotics-related users or businesses (if I have something thoughtful to add, not just ‘nice post’)

If I stick to all of those things, I think I’ll see a big boost in traffic. My goal is to double the number of impressions I hit last week.

The other update from the week is that I had someone sign up for the mentorship program! I start working with them this week. So I will be spending some of my time this week working with that client. Hopefully I will have more to say about what I’m learning from the mentorship part of the business sometime soon.

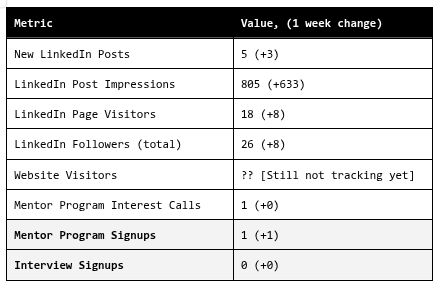

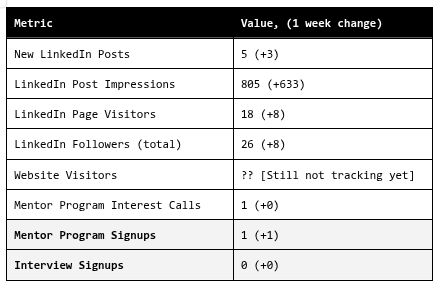

Here are the stats for the week:

Until next week,

Jake

January 17, 2026 at 1:15 PM

Classics

Moby Dick - Herman Melville: Reading this book I kept thinking to myself, “how is it possible that a human mind managed to put all of these words together? How does that sentence come into a person’s head? I could spend a year and not produce one paragraph like this, and he’s come up with 500 pages!” The opening chapter of Moby Dick is one of my all-time favorite bits of prose. This is by no means a ‘can’t-put-it-down’ book in terms of the plot, and is probably one where I’ll revisit specific chapters, rather than reread it from start to finish. Not that I didn't enjoy the plot, and the symbolism of the white whale and Ahab and the voyage will stick with me, but this is a book you read first and foremost for the words.

Yes, there is death in this business of whaling—a speechlessly quick and chaotic bundling of a man into Eternity. But what then? Methinks we have hugely mistaken this matter of Life and Death. Methinks that what they call my shadow here on earth is my true substance. Methinks that in looking at things spiritual, we are too much like oysters observing the sun through the water, and thinking that thick water the thinnest of air. Methinks my body is but the lees of my better being. In fact take my body who will, take it I say, it is not me.

…

there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.

Meditations - Marcus Aurelius: I enjoyed reading this - I read most of it at the gym during the breaks between sets. It’s a collection of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius’s personal journals and is composed of many short entries (a few sentences to a few paragraphs), without any narrative or overarching theme, so it lends itself to being read in little bits. There are some great nuggets of wisdom throughout, but beyond that I just found it fascinating to see how the most powerful person in the world 2,000 years ago was thinking about essentially the same existential questions we all grapple with today.

For Whom the Bell Tolls - Ernest Hemingway: This was the first selection of my new ‘classics’ book club, which I intend to continue throughout this year. It was the second Hemingway novel I’ve read, the first being The Old Man and the Sea which I listened to as an audiobook all in one go. I loved this book. It takes a little while to get going, but then builds and builds all the way to the end. The Roberto-Maria storyline felt rushed and unnecessary, and Maria in particular wasn’t really given any agency, but the rest of the characters and relationships were compelling. El Sordo on the hill was an unforgettable scene.

Other

The Familiar - Leigh Bardugo: A contemporary historical fantasy novel. Wasn’t for me.

The Ministry of Time - Kaliane Bradley: A contemporary sci-fi novel. Also wasn’t for me.

The City and the City - China Miéville: A 2009 sci-fi novel winner of the Hugo prize. I liked this one significantly more than the other contemporary fiction I read last year. The premise was unique and thought-provoking, and while I didn’t love the ending, the bulk of the book was good enough that I’d still recommend it.

The Deep Places - Ross Douthat: This book captures, better than anything else I’ve read, the experience of living with chronic illness/pain. Douthat recounts how he went from being an ordinary, thriving adult, to having his life up-ended by [what he believes was] chronic lyme disease, and the extreme lengths he went to in an effort to make the pain stop. I had a similar experience after college (things were never as bad for me as what Douthat describes) where chronic pain dominated my life for a few years, and it was cathartic to see many of my own thought patterns mirrored by Douthat.

In the same way that “we filter for people who are like us intellectually and politically,” he [Scott Alexander] wrote, “we also filter for misery,” so that the suffering around us passes unheard and unseen.

To get sick and fail to get better is to realize the harsh truth of this insight. Human beings have a great capacity for kindness, empathy, and help, but we are more likely to rise to the occasion when it is clearly an occasion—a moment of crisis, a time-bound period of stress. In the aftermath of a hurricane, society doesn’t usually fragment; it comes together in solidarity and support. Likewise with families and individuals facing suffering in the moment that it descends, or when a terrible arc finally bottoms out: Not always, but very often, people behave well, with great generosity, in the face of a mortal diagnosis, a mental collapse, an addict’s nadir. Not least because in those circumstances there are things you can clearly do, from the prosaic—making frozen dinners for a suffering family—to the more dramatic and extreme, like flying across the country to help drag a friend into rehab.

But when the crisis simply continues without resolution, when the illness grinds on and on—well, then a curtain tends to fall, because there isn’t an obvious way to integrate that kind of struggle into the realm of everyday life. It’s not clear what the healthy person is supposed to give to a friend or family member who isn’t dying, who doesn’t have some need that you can fill with a discrete act of generosity, but who just has the same problems—terrible but also, let’s be frank, a little boring—day after depressing day.

“Pain is always new to the sufferer, but loses its originality for those around him,” the nineteenth-century French writer Alphonse Daudet wrote” … “Everyone will get used to it except me.”

I’m dubious of his theories about what was really going on with his body, and extremely dubious of some of the treatments he pursued (though I absolutely relate to the desperation that led him to pursue those treatments), but those aren’t the reasons to read this book. The reason to read the book is to understand what it’s like for a person to be in pain all of the time and not know how to make it stop.

The Way Out - Alan Gordon: A very different book about chronic pain, this one by a doctor who has helped many patients recover from chronic back pain by (in my opinion correctly) treating it as dysfunction of the nervous system rather than solely, or even primarily, as a structural problem. I had not read this book during my earlier run-in with chronic pain, but the ideas Gordon explains are consistent with the things that eventually worked for me. If you’ve been dealing with chronic pain (pain that’s continued long beyond an initial injury or has no clear cause, and occupies a lot of space in your mind), I’d recommend this book.

Feel Good Productivity - Ali Abdaal: I bought this one because I’ve watched many of Ali’s YouTube videos on productivity, motivation, and business and think he usually has good advice. The book was fine, it’s got plenty of good ideas and experiments to try, but it does feel like it’s written by a YouTuber. I don’t think there was anything in it that you wouldn’t find on his YouTube channel and I think he’s more effective in that medium. You could read this one in a day or two if you wanted though, so if you’re just looking for a quick infusion of ideas to get out of a rut or something, it might be helpful for you.

January 11, 2026 at 2:30 PM

At the end of 2024 I started an in-person history book club in order to motivate myself to read a bunch of history books. We went through 7 books over the course of the year (one was a DNF due to the book being terrible), covering a diverse set of topics.

The book club has been a success - I had no idea if anyone would sign up and now we’re up to about 140 members (of which maybe 20 or so are active), and it did indeed get me to read lots of books that I otherwise would not have read. All the meetings had at least 5 attendees and there seems to be a core of regulars. I’ll write another post sometime with more reflections on the book club, but here I’ll run through the books we read and my brief thoughts on each one.

Everything Under the Heavens - Howard W. French: Not bad and not too long, but not the best choice for your first book on Chinese history, which it was in my case. This book surveyed China’s relationship with most of its neighboring countries, in each case going back in history and then working up to the present to show how events of the past shape the current relationship. It did a fine job of what it was trying to do, but was more focused on specific, modern issues and how they came to be rather than primarily being a history book, which made it an imperfect choice for my book club.

The Three Emperors - Miranda Carter: Covered the lives of King George V (plus a lot of Victoria and Edward VII), Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Tsar Nicholas II, all of whom were of similar age and reigned as monarchs in their countries during the onset of WWI. The most interesting theme was the way that Britain, Germany, and Russia differed in how much ‘real power’ their monarch had at the beginning of the 20th century, and the problems this caused, particularly in Russia where there was a very weak parliament and the tsar had mostly unchecked power. The book went into extensive detail on the minutiae of each monarch’s life which I found tedious. I would also recommend reading some other primer on the buildup to WWI before reading this book. This book gives an interesting viewpoint for analyzing WWI, but focuses mainly on the lives and relationships between the monarchs and other government officials and I found it hard to connect these to the larger context.

Inventing Japan - Ian Buruma: This was a non-book club selection that I chose because I was looking for an introduction to Meiji-era Japan. It's a short book and does indeed give an introduction to Meiji-era Japan, but it wasn’t exactly what I was looking for. I think it assumed more background than I had, so a lot of it went over my head. The writing style was a bit odd as well. I don’t anti-recommend it, but you may be better off trying something else if you’re interested in the subject.

SPQR - Mary Beard: A broad survey of Roman history and an excellent book. It covered a large timespan (which was what I wanted, being new to Roman history) and was both accessible and thorough. She did an excellent job of differentiating between “what we know definitely happened,” “what we think might have happened or have only a fuzzy picture of,” and “what is pure speculation / legend.” In addition to being a great book on Roman history, it was also a great book for learning how we learn about antiquity at all, the information sources we rely on for this era (sometimes we’re trying to infer a great deal from a fragment of an inscription on a tombstone) and the pitfalls ancient histories can have (written to legitimize the current ruler and/or denigrate prior rulers).

The Anarchy - William Dalrymple: A history of the British East India Company and how it gradually amassed control over all of India. Interesting throughout, it spent more words than necessary on a number of different battles, but the broad story was well-told. One interesting idea was that, indirectly, the American Revolution had a major impact on Indian history by prompting the British to change tactics in India to avoid a similar outcome. I was also surprised at how independently the East India Company acted. I had the impression that the colonization and conquest of India was a project of the British government, and that the EIC was just a vehicle for accomplishing it, but it seems that really was not the case in the beginning. The EIC raised armies, built cities, established local governance, often while actively hiding its actions from the British government. If anything, the government was holding the EIC back for the first hundred years or so.

The Silk Roads - Peter Frankopan: A very broad history of much of the world, with a loose focus on the Middle East and the way the dominant trade routes (“silk roads”) of different eras shifted the balance of world power. This is a great choice if you’re new to reading history, given its breadth, though that also means it doesn’t go especially deep on any one topic. The 'Silk Roads' framing of the book was forced and unnecessary, but didn't really detract anything. One thing that stood out to me was the way that (1) demand for prized goods from India and China led to sprawling trade routes between Europe and Asia, (2) control of those trade routes concentrated wealth in the most powerful cities along the routes, and (3) desire to circumvent those ‘middlemen’ and gain direct access to eastern goods spurred innovation which eventually irrevocably upended the world order. Countries like Spain and Portugal began the 'Age of Exploration' because sea routes were the only way for them to gain unrestricted access to eastern goods. And then England followed suit and leapfrogged them, likewise forced by their powerful neighbors to innovate further. The accidental discovery of the Americas and the enabling technological innovations had the side effect of elevating those countries to power at a pivotal moment in history.

[DNF] Debt -David Graeber: Utterly incomprehensible. I think I disagree with most of the author’s ideas but it’s difficult to say for sure because I don’t think he is himself clear on what his ideas are and the book doesn’t have any kind of logical structure. I voted for this book in our book club poll thinking it would be some kind of history on the evolution of debt (I know, how foolish of me to think that of a book titled “Debt: the first 5,000 years”), but in reality it was a mashup of philosophy / political treatise / anthropology with only a bit of (dubious) history, and does none of those things well. I gave up about half way through. Everyone in my book club who had made significant progress on the book also thought it was terrible. Anti-recommend.

1776 - David McCullough: An excellent read to end the year, and the first American history we read for the book club. This was a notably different style of book from our other selections, focusing on a much narrower subject (the American Revolutionary War, specifically in the year 1776) and told mostly through first person accounts by prominent figures in the conflict. I was dubious for about 10 pages and then I was hooked, this was the most “can’t put it down” history book I read during the year. The book focused on the three major events of the war in 1776, the siege of Boston, the battles in and around New York, and Washington’s crossing of the Delaware. I had not realized how dire the situation was at the beginning of the war. It really does seem that if not for a handful of very specific decisions (timely retreats, the Delaware crossing, Howe’s conservatism), Britain would have simply wiped out the Continental Army, forcefully suppressed the rebellion, and … who knows what history would look like from there.